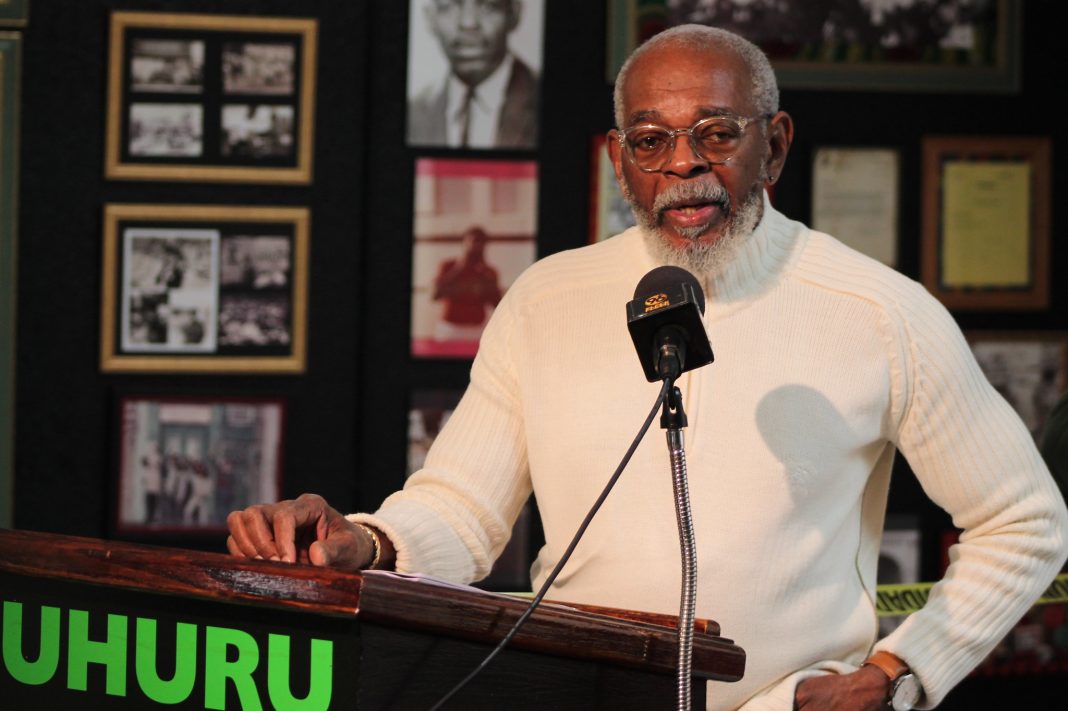

In the 21st century, terms like “colonialism,” “systemic oppression,” and “anti-Blackness” have become increasingly prevalent in academic, media, and activist circles. However, few acknowledge the intellectual origins of this analytical framework regarding the lived reality of African people around the world. This paper contends that Chairman Omali Yeshitela, founder and leader of the African People’s Socialist Party (APSP), has made foundational contributions to this discourse through his development of African Internationalism—a political theory that redefined colonialism as a present and enduring system rather than merely a historical phase.

African Internationalism fundamentally challenges liberal frameworks by asserting that African people are not a racial minority but a colonized nation, whose forced dispersal across continents due to slavery and colonialism laid the groundwork for modern capitalism. This theoretical intervention repositions racism as not the root cause of oppression but rather as the ideological superstructure of a deeper colonial relationship. In this reframing, colonialism evolves beyond foreign policy to become the foundational structure of political economy that undergirds Western society.

Naming the system and locating the power

Yeshitela’s theoretical framework emerged from decades of organizational experience and represents a significant departure from both liberal civil rights approaches and traditional Marxist analysis. African Internationalism posits that the primary contradiction in global capitalism is not between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, but between colonizer and colonized nations. This analysis identifies African people—whether in Africa, the Americas, or Europe—as a single colonized nation whose resources, labor, and cultural production serve as the material basis for Western wealth and development.

The theory’s emphasis on naming systems of power reflects Yeshitela’s understanding that ideological clarity precedes effective resistance. By identifying colonialism as the organizing principle of contemporary global relations, African Internationalism offers a framework for understanding phenomena that liberal discourse often treats as separate issues: police violence, mass incarceration, economic disinvestment, cultural appropriation, and neocolonial foreign policy.

Colonialism as a mode of production

Chairman Yeshitela’s most significant theoretical contribution is his identification of the colonial mode of production as the foundation of global capitalism. This concept frames the relationship between colonizers and the colonized not only in terms of territory but also in terms of structural economics. Throughout history, African people have served and continue to serve as the material base of Western wealth and development. This theoretical framing builds upon and extends the work of scholars such as Frantz Fanon and Walter Rodney. While Fanon explored the psychological dimensions of colonial domination and Rodney demonstrated how Europe systematically underdeveloped Africa, Yeshitela enhances this analysis by identifying the ongoing existence of colonialism within settler states such as the United States.

Within this framework, the African working class in the United States remains unincorporated mainly into American society. Still, it constitutes an occupied population managed by militarized police forces, contained through mass incarceration, and economically exploited through systematic disinvestment. This analysis explains why traditional labor organizing often fails to address the specific conditions facing African workers, who occupy a colonized rather than an exploited relationship to capital.

The concept of parasitic capitalism, developed by Yeshitela, sheds light on the relationship between capitalism and colonized nations by highlighting how the capitalist system manifests itself through the extraction of value from these nations, without providing any reciprocal investment or development. This perspective directly challenges liberal narratives that portray capitalism as a system capable of reform or as a force for globalization.

Mainstream appropriation and theoretical influence

Over the past decade, there has been an observable diffusion of Yeshitela’s conceptual frameworks into broader public and academic discourse, though often without proper attribution. The widespread adoption of colonial analysis to describe domestic systems of racial oppression, critiques of capitalism as fundamentally extractive, and demands for reparations have gained traction on mainstream platforms, including academic conferences, political campaigns, and popular media.

This theoretical influence can be traced through various intellectual and cultural channels. Public intellectuals and media figures have increasingly adopted language and analytical frameworks that echo African Internationalist principles. The growing prominence of terms like “settler colonialism” in academic discourse, the mainstream adoption of reparations as policy discussion, and the analysis of racism as structural rather than individual all reflect conceptual groundwork laid by Yeshitela’s theoretical contributions.

In academic institutions, courses in ethnic studies, postcolonial theory, and Black studies are leaning toward approaches that closely align with Yeshitela’s lessons, particularly regarding race, economics, and state violence. For instance, the concept of “racial capitalism,” as introduced by scholars like Cedric Robinson, echoes the earlier thoughts of Yeshitela on the parasitic nature of economic systems. However, African Internationalism maintains a sharper focus on African self-governance and national liberation, distinguishing it from academic approaches that may lack organizational praxis.

The influence extends beyond academic circles into popular culture and social movements. Contemporary discussions about cultural appropriation, critiques of “diversity and inclusion” initiatives as inadequate responses to systemic oppression, and analyses of policing as a form of colonial occupation all reflect analytical frameworks developed within African Internationalist theory.

Cultural commodification and the colonial superstructure

A critical area of African Internationalism examines the intricate relationship between culture and the perpetuation of structured economic violence. Yeshitela says that although Black culture is dynamic and has a global reach, it is systematically appropriated and commodified by colonial institutions. This commodification process strips cultural production of its political content and rebrands it as entertainment or an aesthetic commodity.

This phenomenon is evident across various industries. In music, African American innovations in hip-hop, R&B, and other genres generate billions in revenue, while the communities that created these forms often remain economically marginalized. The fashion industry similarly appropriates African and African American aesthetic innovations—from hairstyles to clothing designs—while excluding Black designers and communities from ownership and profit. Social media platforms monetize African American vernacular and performance styles, while algorithmic systems often suppress content created by Black users.

The entertainment industry offers perhaps the clearest example of this dynamic. Black cultural production significantly drives portions of American entertainment revenue, yet ownership and control of production, distribution, and exhibition remain concentrated among non-Black corporate entities. This creates what Yeshitela identifies as a colonial relationship, where cultural resources are extracted from colonized communities for the benefit of colonizing institutions.

Yeshitela’s solution goes beyond mere calls for representation or cultural recognition. Instead, African Internationalism insists on control over the institutions of cultural production—radio stations, newspapers, film studios, educational institutions, and community economies. The APSP’s practical work, including the Black Power 96 FM radio station and the Uhuru Movement’s economic development initiatives, illustrates this principle by building independent institutional capacity within colonized communities.

Solidarity and the challenge to white liberalism

African Internationalism’s approach to solidarity represents a fundamental challenge to liberal models of allyship and coalition-building. Through organizations like the African People’s Solidarity Committee (APSC), chaired by Penny Hess, the theory demands that members of the colonizer class confront their material relationship to colonialism and engage in reparations work under African leadership.

This model rejects symbolic gestures or guilt-based responses to colonial oppression. Instead, it requires white people to acknowledge that their wealth and social position—regardless of personal politics or intentions—derive from ongoing colonial extraction. Penny Hess’s work in Overturning the Culture of Violence details how white wealth accumulation, including that of liberal and progressive whites, remains structurally dependent on colonial relationships.

The APSC and Uhuru Solidarity Movement (USM), led by organizers such as Jesse Nevel, engage white people in returning material resources to the African community and are dedicated to dismantling white power structures. This process is specific and asserts that action is required, not merely abstract solidarity. The action necessitates that individuals relinquish their power to African leadership and make material reparations. This model of solidarity sharply contrasts with traditional allyship approaches that often emphasize white comfort and moral absolution. African Internationalism’s framework of solidarity is based on political accountability, material redress, and strategic subordination to the leadership of the colonized. Genuine solidarity demands challenging the material foundations of the colonial relationship, rather than just sharing opposition.

Organizational praxis and theoretical development

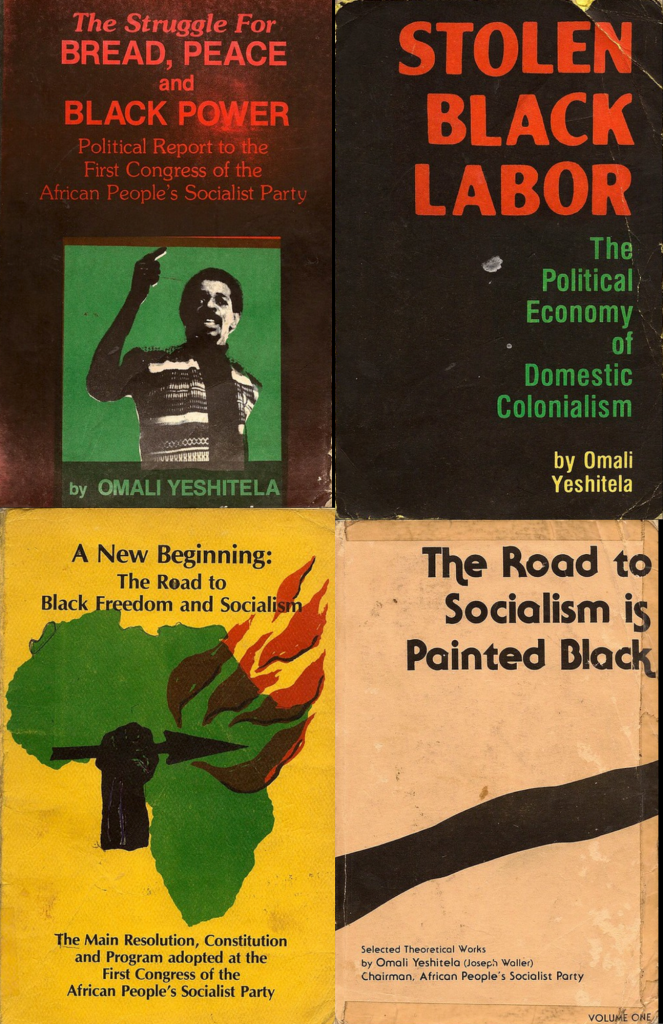

The strength of African Internationalism as a theoretical framework is rooted in its evolution through continuous organizational practice. The African People’s Socialist Party has engaged in consistent political work over multiple decades, allowing theoretical insights to be tested and refined through practical application since its establishment in 1972.

The APSP’s work encompasses various dimensions of anti-colonial struggle. Economic development initiatives, such as the Uhuru Movement’s community programs, showcase alternative economic models rooted in collective ownership and black community control. Educational efforts through institutions like Uhuru University foster ideological development grounded in African Internationalist theory. Cultural initiatives, facilitated through media outlets and artistic production, sustain independent platforms for political education and community empowerment.

This integration of theory and practice distinguishes African Internationalism from academic approaches that may lack organizational means for implementation. The sustained nature of the APSP’s work also enables long-term strategic thinking that transcends electoral cycles or movement moments, maintaining consistent anti-colonial analysis across evolving political conditions.

Contemporary relevance and future directions

As global capitalism confronts a deepening crisis and resistance movements emerge worldwide, the analytical framework of African Internationalism offers crucial insights for understanding contemporary conditions. The theory’s focus on colonial relationships clarifies issues that liberal discourse struggles to address: the persistence of racial disparities despite civil rights legislation, the failure of diversity initiatives to combat systemic oppression, and the ways capitalism consistently reproduces hierarchies based on race and nation.

Recent global developments have validated many of African Internationalism’s core insights. The 2020 uprisings following George Floyd’s murder demonstrated the ongoing reality of colonial oppression in black communities and the limitations of reform-based responses. International solidarity movements that connect struggles against police violence in the United States with anti-colonial movements in Africa and beyond reflect the global nature of colonial oppression that African Internationalism has long emphasized.

The framework’s emphasis on reparations as a core demand has gained mainstream political traction, although often in forms that lack the systematic analysis provided by African Internationalism. While discussions on reparations frequently highlight historical injustices, the African Internationalism approach stresses ongoing colonial extraction and advocates for a fundamental restructuring of economic and political relationships.

Conclusion

Chairman Omali Yeshitela’s development of African Internationalism represents one of the most coherent and praxis-oriented frameworks for understanding the persistent structures of global oppression. By conceptualizing colonialism as an ongoing system rather than a historical phenomenon, this theory provides analytical tools for understanding contemporary conditions and offers strategic direction for liberation movements.

The influence of African Internationalist concepts throughout academic, activist, and popular discourse demonstrates the framework’s explanatory power, even as this influence often lacks proper attribution. Yeshitela’s theoretical contributions have transformed the understanding of power, resistance, and liberation, influencing discussions ranging from academic analyses of “racial capitalism” to mainstream debates about reparations in political campaigns. The theory’s combination of clear ideology and practical organization provides valuable lessons for today’s movements. African Internationalism’s emphasis on building independent institutional capacity, challenging colonial relationships at their core, and maintaining a strategic focus on liberation rather than reform guides movements seeking fundamental transformation rather than mere accommodation within existing systems.

As struggles for African self-determination continue worldwide, the work of the African People’s Socialist Party and the theoretical framework of African Internationalism remind us that liberation requires more than moral recognition or symbolic change. Liberation demands ideological clarity, organizational capacity, and material transformation concerning the nature of oppression and the requirements for freedom. It begins, as Yeshitela insists, with naming the system for what it is and building the capacity to transform it.

References

African People’s Socialist Party. (n.d.). Political report to the 7th Congress. APSP Publications.

Fanon, F. (2004). The Wretched of the Earth (R. Philcox, Trans.). Grove Press. (Original work published 1961)

Hess, P. (2000). Overturning the culture of violence: The political basis of the African People’s Solidarity Committee. Burning Spear Publications.

Martin, R. (Host). (n.d.). Roland Martin Unfiltered [Video series]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/@RolandSMartin

Nevel, J. (n.d.). Speeches and writings. Uhuru Solidarity Movement Archives.

Robinson, C. J. (2000). Black Marxism: The making of the Black radical tradition (2nd ed.). University of North Carolina Press.

Rodney, W. (2018). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Verso. (Original work published 1972)

Seales, A. (Host). (n.d.). Small doses [Podcast]. Urban One Podcast Network. https://www.urban1podcasts.com/small-doses

Yeshitela, O. (2005). An uneasy equilibrium. Burning Spear Publications.